The Consolations of Fantasy

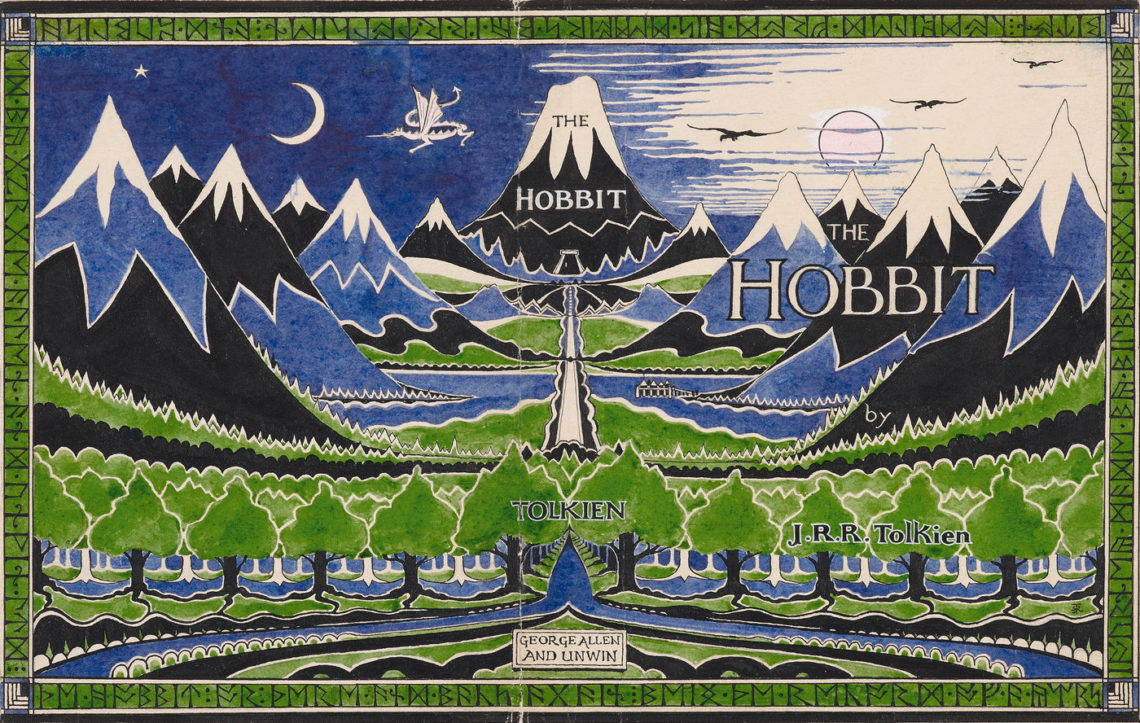

Hobbits, notes J.R.R. Tolkien at the start of their eponymous story, are easily forgotten, largely overlooked, and have little or no magic about them.

Or not. In the 75 years since he penned those words, The Hobbit has sold more than 100 million copies. In its opening weekend, Peter Jackson’s first instalment of the movie version broke records around the world. Clearly there is something a little magical about hobbits after all.

The interesting question, however, is what that magic is. Why should an English boffin’s fairytale of elves, wizards and dragons continue to command such devotion? What craving does it satisfy?

The interesting question is what that magic is. What craving does it satisfy?

To its literary critics, The Hobbit’s success is simply a sign of widespread immaturity. The story, with its faux mediaeval cadences and reactionary archetypes is mere escapism—intellectual comfort-food for the politically disengaged. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, modernists and progressives muttered in protest as this ”juvenile trash” (to quote Edmund Wilson) waxed in popularity and repeatedly won popular votes for most important book and author. A prominent expatriate Australian lamented that Tolkien’s ascendancy was a nightmare come true, and heralded a general flight from reality.

Less dismissive evaluations have tended to major on broader social contexts. Despair in the wake of the world wars and grief over modernity’s failures are frequently offered as explanations for both the book and its reception. From this angle, Tolkien’s works are seen as both a turning away from contemporary evils and as romantic elegy to a (real or imagined) lost world where humans lived in proximity to nature, objects were made by hand, and battles, if necessary, could be fought with honour.

The two assessments, of course, are not mutually exclusive—the second seeks to explain while the first merely judges.

In any case, the social-historical perspective is insufficient. If the appeal of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings were simply a matter of hankering for old times, then surely any historical drama would serve. Why this story? And what part do the supernatural and fantastical elements play in it?

Without doubt, these are questions to which many true answers may be given: Laura Miller’s recent insights concerning the way both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis bring together the homely and wild come to mind; as do Tom Shippey’s observations concerning the importance of Tolkien’s expertise in language.

But we might also do well to pay attention to Tolkien’s own thoughts on what he was doing. In an important essay, On Fairy-Stories , where Tolkien himself seeks to define and defend the fantasy genre, we find him unashamed to allow that it is both escapist and backward-looking. The impulse to escape, he argues, is indeed an appropriate response to the ugliness of the Industrial Age: but it also answers a sense of loss that goes deeper than that. Fairy stories and fantasy speak to the condition of humans separated from God and from other parts of the created order.

Elves and talking animals console humans in their self-wrought alienation from heavenly realms.

Elves and talking animals console humans in their self-wrought alienation from heavenly realms. Fairy stories reassure us that morality will be rewarded and promise-keeping will be vindicated. Magic interrupts the sad patterns and necessities of mortal life with a joyful glimmer that there may still be an intervention from beyond this world—a happy ending, or “eucatastrophe”, as he dubbed it.

None of this means that Tolkien’s work is simply a cypher for his Catholic convictions; he made his distaste for such allegorising clear. But he does believe that all successful fairytales respond to the human predicament as it is described in Christian doctrine. Indeed he will go so far as to argue that the story of Jesus Christ ”embraces all the essence of fairy stories”.

With the concrete historical coming of Christ, the aspiration of the fantasy writer is raised to fulfilment. In the words of C.S. Lewis (who Tolkien converted to Christianity by this very argument) Christianity is the ”true myth” that answers the longing expressed in every successful fairytale and fantasy.

Whether we judge his opinion right or wrong, this is an approach that is capable of taking fantasy literature and its fans seriously. We love The Hobbit, not because we are immature, or because we are sentimental. We love it because it reflects and refracts the deepest—the most real—joys, sadnesses and hopes of being human.