Spooky Stories and the Lord of Halloween

I like a spooky story. Maybe I shouldn’t. Maybe it’s unhealthy. Maybe I should be more reformed and less medieval—more Zwingli and less Luther, as Carl Trueman would put it.

I know there are definite dangers in thinking too much about spooky things—of drifting into a superstitious mindset where intermediate powers control the ups and downs of life. I know that I am not immune to that temptation, and I know the antidote (see more here).

I like the idea that there is a hidden world that still reveals itself.

I’m also unsure of how many of the stories one hears are genuine. I have had a few strange things happen to me. I have felt myself wordlessly assailed in the night before giving a talk or teaching session. I once woke up paralysed, with a sense of a dark shadow standing next to me. But these phenomena are vague enough that I cannot be absolutely sure of whether they are coming from me or beyond[1]—though the fact that prayer and praise dissipate them might indicate something. If I can’t be sure of my own intuitions, I trust others’ less.

Nonetheless, I like a spooky story. I like the idea that there is a hidden world that still reveals itself—even when that revelation is malign. I like (plausible) spooky stories because they disrupt the arrogant certainties of scientific materialism and fit with the ornate cosmos I see revealed in the Bible: a world of angels and demons and spiritual powers and unclean spirits (whatever they are).

The World of Confusion …

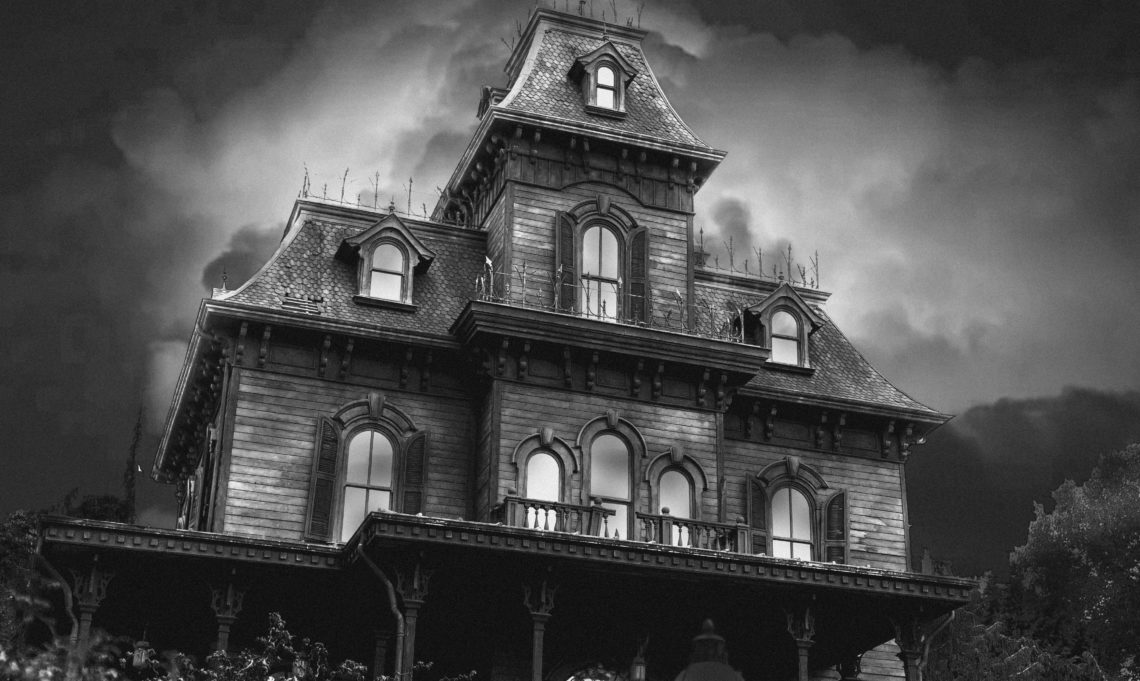

This doesn’t mean that I expect anyone to be convinced of anything useful by spooky stories. In recent weeks, I have been listening to Otherworld—a curated podcast that collects first-person accounts of all kinds of weird and wonderful experiences ranging from encounters with cryptids (Bigfoot, etc.) to weird timeshifts and hauntings. Some of these stories are more credible than others, but none of them produce any clarity. When the paranormal entities purport to enlighten, they deliver platitudes (pursue peace!) or disinformation (reincarnation etc.). Sometimes, they will do an unconvincing job of passing themselves off as aliens. Often, they just seem hostile.

The spiritual world is the home of confusion—perhaps even of insanity. And this, too fits with the testimony of Scripture. It fits with the weird phenomenon of evil spirits shouting Jesus’ identity as Son of the Most High, or going into pigs and then drowning them (Mark 5:1-13); or declaring the future (Acts 16:16—goodness knows how that worked).

… And the King of Glory

But it is also a world that gives way before Jesus. As we read the Gospels, we see that his power over these entities is absolute. We learn, too, that he is willing to share that power with those who act in his name (Luke 9:1).

And that gift is still available. One of the most frustrating things about listening to the Otherworld podcast is how the host consistently fails to notice when Christian prayer decisively resolves a problem: nobody wants to stay in a certain hotel room (the site of a suicide) until the cleaning staff hold a prayer meeting in there; one couple experiences poltergeist-like disturbances until her minister father comes and prays in the house.

I suppose there are complicating factors. Non-Christian measures sometimes seem to work a bit too. And not every use of Jesus’ name is guaranteed to work (c.f. Acts 19:13-17). Nevertheless, the lack of curiosity about this aspect of the supernatural seems telling.

The deeper answer, of course, is that raw signs and wonders have never been very good at providing clarity—even in the ministry of Jesus. People see the show and provide their own interpretation: ever seeing but never perceiving (Matt 13:14). People will go to great lengths to avoid drawing inconvenient conclusions (Mark 3:23). Perhaps, like me, you have seen some contemporary examples of this.

Only Jesus himself brings clarity to these matters—and not by answering all our questions, but by transcending them. He is the one who created all these invisible entities (Col 1:16). He is the one who terrified them on earth, and now rules over them from heaven (Eph 1:20; 1Pet 3:22). As we turn to Jesus, we press into the unseen world in an entirely different way; not in fear and confusion, but in joy and confidence:

… You have come to thousands upon thousands of angels in joyful assembly, 23 to the church of the firstborn, whose names are written in heaven. You have come to God, the Judge of all, to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, 24 to Jesus the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel. (Heb 12:22-24)

From fools Paradise to Eternal Comfort

Finally, it is worth observing that it is a luxury to be able to enjoy the thrill of spooky tales. We can enjoy the creepiness of fictional (or possibly true) ghost stories as long as we don’t feel in personal danger. But people in other parts of the world live in terror of them: their lives and sleep are disrupted; they spend their precious resources on charms and appeasement. It was the advent of Christianity—especially Reformation Christianity—that banished all that to the margins. The Enlightenment inherited a house swept clean (let the reader understand; Luke 11:24-27).

But it is one thing to feel safe from these things because we know Jesus is infinitely greater than them. It is quite another thing to treat them lightly because we don’t believe in them or recognise their dangers. With superstition and spiritism on the rise in the religion-starved West, quite a few people are going to find out that they have been living in a fool’s paradise. Maybe believers will find themselves bumping up against these things, too.

If so, there is great news for all of us. Jesus is still Lord; the same yesterday, today and forever.

[1] Skeptics would certainly insist that the sleep-paralysis experience is widespread and merely physiological. Perhaps, but the first need not connote the second.