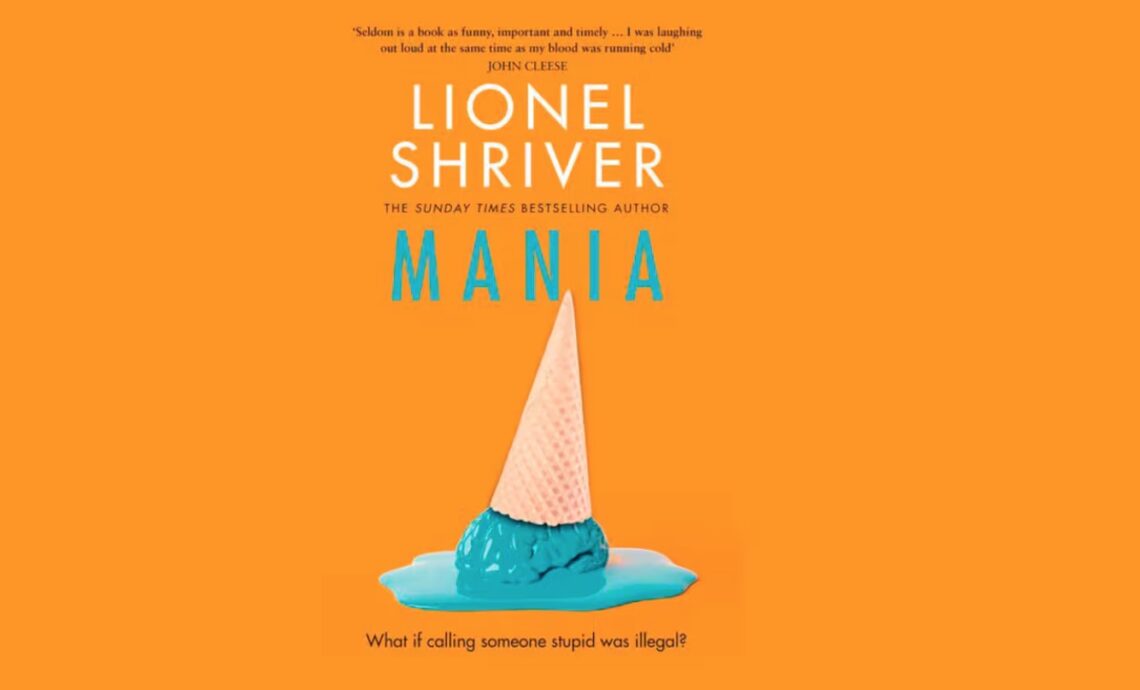

Review: Mania by Lionel Shriver

(Contains spoilers for Lionel Shriver’s novel Mania)

Cognitive discrimination has been outlawed in the America of Lionel Shriver’s novel Mania (2024). Nobody is stupid, everyone’s brain is equal; the country is falling apart.

Mania opens with Pearson Converse, the story’s protagonist, being summoned to remove her son from school after he used the “D-word” about the slogan on another child’s t-shirt. The Principal is unyielding:

“Playground obscenities would be one thing. Slurs are quite another. This is a suspension level offense. Any similar violation in the future could merit expulsion.”

Pearson initially complies, and teaches her children to hide what they really think. But she is unable to follow her own advice for long. Before the end of the book, her inability to fall in line will have destroyed her academic career, her marriage, her relationship with her children and her oldest friendship. In the background of this alternate history, the Mental Parity Movement (MPM) erodes medical and military standards, alters language (no more “smartphones”) and replaces an educated President with less offensively bright candidates (hilariously, those of the real-world present).

Mania is an attack on political correctness itself.

This is satire, of course, but it is not difficult to see what Shriver has in mind. The cocktail of radical egalitarianism, virtue-signalling and censorship by bureaucracy is too familiar. Mania is an attack on political correctness itself.

An Ongoing Campaign

This is part of an ongoing campaign for Shriver. Australian readers may remember how she openly courted progressive outrage in 2016 when she donned a sombrero at the Brisbane Writers Festival and denounced the idea of “cultural appropriation”. In more recent years, she has fired broadsides at hate speech legislation, transgenderism, unfettered immigration and the cowardice of public apologies. Shriver is a (near) free-speech absolutist, a liberal of the stripe that is now dubbed libertarian or contrarian (or “far-right” by the radical left).

Judging people according to their attributes really does produce toxic hierarchies of privilege.

It might be tempting then, to see Pearson Converse as a self-insertion and Mania as simply propaganda. Yet that would do injustice to Shriver’s skill as a novelist and her nuance as a thinker. Mania acknowledges the ugliness of those who prize intelligence too highly as well as the moral poverty of those who want to ban it. Pearson’s decision to have children by a highly educated sperm donor is labelled eugenic. The novel shows how her preoccupation with their intelligence destroys her relationship with her less gifted natural daughter. Later in the story when the backlash happens, we see “cognitive parity” give way to a discriminatory meritocracy that turns out to be just as subject to groupthink and grift.

This raises difficult questions. Pearson’s answer is to commend a more holistic way of seeing people:

Many qualities distinguish us besides mental endowment. Generosity, loyalty, kindness, and common sense. The capacities for wonder and joy. A sense of humour. A sense of honour. Grace, clemency, and candour. Diligence, conscientiousness, and a willingness to sacrifice for others. Smart people can be intolerable, while many a buddy with a middling intellect is still great company and may go to the ends of the earth to save your bacon.

This seems like wisdom—especially in this monocular age where we are all reduced to cardboard cutouts of the latest critical paradigm: class, sex, gender, race etc. However, diversifying the criteria doesn’t quite resolve the more basic problem. Judging people according to their attributes, though it might be useful in job interviews, really does produce toxic hierarchies of privilege. The rich, beautiful, confident and charismatic (far more than the merely intelligent) always end up with extra pie. The poor, ugly, depressed and awkward fall between the cracks.

Not the Way it’s Supposed to be

This is not the way it is supposed to be. We are supposed to see each other as equal, not because we have equal abilities, but because God made us in his image (Gen 1:26-28)—a designation that refers not primarily to attributes but to our being God’s representatives. We are valuable simply because God says we are; we come invested with a measure of his dignity and his honour. Thus Scripture warns that:

Whoever sheds human blood, by humans shall their blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made mankind. (Gen 9:6)

And

…whoever is kind to the needy honours God … Whoever mocks the poor shows contempt for their Maker (Prov 14:31; 17:5)

And

With the tongue, we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness … this should not be. (James 3:9-10)

God is no more impressed by our intelligence and class than he is by our virtue—indeed he deliberately chooses the unimpressive to make the point:

Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. (1Cor 1:26-27)

Without this theological perspective, we are stuck with the dichotomy of pretending there are no differences between people or making too much of them. The first will destroy our minds; the second will shrivel our hearts.

An Angry Book for Angry Times

Mania is an angry book for angry times—and this is not a criticism. It is surely appropriate to feel indignant when common sense is banned and when hard-won freedoms are sold off to appease ideological extortionists. If Shriver makes people more resistant to censorship (and self-censorship), her novel will have achieved a worthwhile objective.

Yet “human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires.” (James 1:20) Mania has no plausible solution to the problems it identifies. For that we need a totally new way of assessing ourselves.

So from now on we regard no one from a worldly point of view. Though we once regarded Christ in this way, we do so no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come … (2Cor 5:16-17)